|

One of the most common questions I am asked is “What is the difference between SSI and Disability?” This is an important question that can have a significant impact on the amount of benefits awarded, or even whether there is an award at all.

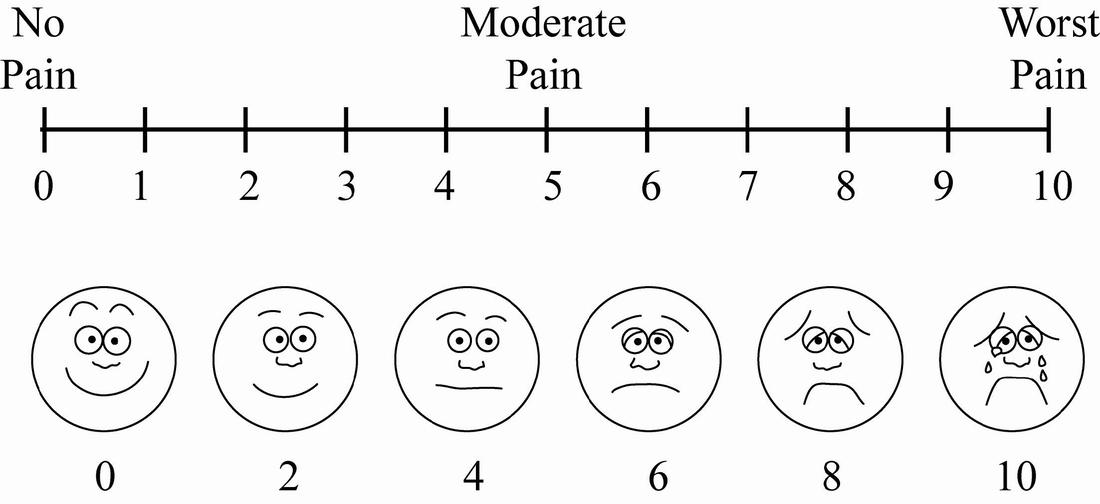

I like to explain “disability” benefits (also called SSDIB or OASDI) as an insurance program. When you have money withheld from your paycheck for Social Security, these payments act like insurance premiums. The amount that you pay into the program throughout your working life determines the amount of benefits that you may receive. The important thing to remember about these payments is that for disability purposes, your insurance coverage can expire. From the date that you become disabled under the medical rules, SSA will look backward ten years (which is equal to forty “quarters of coverage”). Within that ten year period, you have to have twenty quarters (five years) of coverage. To oversimplify, if you haven’t worked within the five years before you became disabled, you are not covered for disability benefits. It doesn’t matter that you worked for many, many years prior to the end of your working days; you still have to be covered during that period to receive benefits. These rules result in seemingly harsh results for stay at home parents or someone caring for sick relatives, who often lose their coverage. It also makes life more difficult for folks who file their claim for disability several years after the onset of health problems. Supplemental Security Insurance (“SSI”) does not require quarters of coverage. The financial eligibility for SSI is based on poverty. If you have very little income and very few assets, you may be eligible. The maximum amount of assets that you can own and be eligible is $2,000 for an individual and $3,000 for a couple. Fortunately, the home in which you live and your vehicle do not count toward that asset cap. There are more exemptions listed here: https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-resources-ussi.htm. Unfortunately, any pension or retirement assets do count toward the asset cap. Income eligibility for SSI is more complicated. There is a list of exempt income at https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-income-ussi.htm, along with some other information about the program. To oversimplify, most non-work income acts as a dollar for dollar offset from SSI benefits. So, if you have a small retirement benefit of $200 per month each and every month, your SSI would be reduced by $200. If you are able to work for limited hours, then your work income acts as a fifty percent reduction in SSI. So, if you earn $300 per month, your SSI would be reduced $150. (There is also a $65 monthly waiver from work income, not included in this explanation, just to make things more complicated). In 2021 the base SSI amount is $794. Check here for the amounts for other years https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/COLA/SSI.html. The distinction between these programs is sometimes difficult to identify because most folks apply for both benefit programs at the same time. The Social Security Administration is pretty good about inquiring if you want to apply for both of them. Many folks with whom I speak don’t remember applying for both programs. The other thing that may be confusing is that medical eligibility for both programs is the same. If you are sick or disabled enough for one program, then you are sick or disabled enough for the other. The difference is in the financial eligibility. You must meet the financial eligibility for one or the other, regardless of how sick or disabled you are. In other words, if you do not have the quarters of coverage to be eligible for disability insurance, and you have too many non-exempt assets to be eligible for SSI, then you will not be eligible for either program despite the severity of your health problem.  Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Source: Yale.edu Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Source: Yale.edu You have probably been asked by a doctor to “rate your pain on a scale of 0-10” before. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is a tool to track trends in your pain level. It can be difficult to know how to put your pain into a number, but doing so can show a clearer picture of what you’re dealing with and how to treat it. It can also show how your pain may change throughout the day, months, or year. Because of that, it is very important for you to be as accurate as possible in converting your pain into a number on the pain scale. Try to think of the numbers on pain scale as the only numbers that possibly exist to quantify your pain. If your pain is at a 1 or 2 out of 10, it would mean that you have some pain that is noticeable, but you can generally function somewhat normally and "push through" the pain. Since "10" is the highest number that exists on this scale, your pain level being at a 10 out of 10 would mean you are so incapacitated from your pain that you need to have someone call an ambulance, or that you cannot walk or sit up due to the pain, or that the pain is making you vomit. It is not helpful to rate your pain outside of the 0-10 pain scale, such as saying your pain is “15 out of 10.” While it may seem obvious that you are making the point that your pain is worse than it has ever been, rating your pain above the 0-10 scale will make people think that you are not accurately reporting your pain, or worse -- that you are exaggerating or drug-seeking. This can make you appear not to be believable witness to Social Security. One thing to keep in mind in reporting your pain levels is not to avoid using absolutes like “never” or “always” when talking about your symptoms. Telling a doctor that your pain “never” goes away, for example, may not be accurate. While it may be true that you do always experience some degree of pain, if you are able to explain to the doctor that certain activities can make your pain better or worse it does give the doctor a great deal more information and it also helps you to be more credible. It can be very helpful to describe the pain that you feel in different parts of your body separately and in terms of both what your “average daily” pain is and also what your “worst pain” is. For example, you have lower back pain that you would generally rate as 3 out of 10 on an average day. Sometimes it will go as high as 8 out of 10 on days when you’ve had to be on your feet longer than normal or when you’ve been engaging in a lot of activity. Keep track of anything that will help to reduce your pain, even if it does not make the pain go away entirely. If things like taking a hot bath, sitting in a recliner with your legs elevated, or taking pain medication does help your pain level to subside somewhat, try to think about how you would rate your pain after doing these things and to put that into a number that might be different from your worst pain. Workplace Jargon: "One-Three-Five"The Social Security Administration may not try to win all of its cases, but it does keep a lid on employee bonuses

Matt Taibbi Nov 19 Every job has its own language. “Workplace Jargon” is a new feature in which employees from a variety of fields — public defenders, doctors, miners, mental health counselors, members of the military, etc. — talk about the vocabulary of their careers, and the sometimes-irrational bureaucracies that rule their work lives. An attorney for the Social Security Administration — we’ll call him Sam — was invited to a regional management seminar. “It was a two-day event, and most of it was meetings and discussions,” he recalls. “But in one small part of it, they showed a little video.” The video, he recalls, showed actors in the roles of SSA managers and employees, playing out various common workplace scenarios. The concept of the video was to show managers how they might best handle tricky situations. In one section, Sam says, “they had an ‘employee’ asking how to improve his work evaluation.” Background: most of the Administration’s 66,000 employees are graded once per fiscal year using “PACS,” or the “Performance Assessment and Communications System.” Under “Interpersonal Skills,” “Participation,” “Demonstrates Job Knowledge,” and “Achieves Business Results,” employees may receive one of three scores — a one, three or a five. As Sam explains. “A one means, ‘Does not meet expectations.’ A three means, ‘Meets expectations.’ And a five means, ‘Exceeds expectations.’” He notes that, "People mostly get threes.” In the acronymized hell that is service in an organization as large as the SSA, one may achieve a bonus called an ROC (Recognition of Contribution) for doing well on these evaluations. Specifically, getting two fives in the same evaluation earns kudos and sometimes also a small financial reward. Meanwhile, poor performance might force superiors to attach to you the yoke of shame known as an “OPS” or “Opportunity to Perform Successfully,” a kind of improvement plan that has to be worked off to put the employee back in good standing. Sam was watching the video with, at best, mild interest, when he saw something odd. “In one case, the question came up, ‘What do we do when an employee asks how they can get a 5?’ he recalls. “They had the actor playing the employee asking things like, ‘What can I do to improve from a 3 to a 5? How can I meet that standard?’” Sam pauses. “And the directive was basically, don’t tell them how they can improve. Managers were told to say things like, ‘I can show you the manual that explains the ratings…’ Basically, they were hiding the ball — actively not telling employees how they could do better.” He pauses. “I looked around. Not a single person objected. There was no pushback.” Why not help threes become fives? Sam speculates that maybe managers are worried about litigation, i.e. “You told me I needed to do this to become a 5, and I didn’t get it.” (There have been lawsuits involving the SSA and PACS). Maybe it was a monetary issue involving bonuses, although Sam thinks that’s unlikely. Mostly, he says, the SSA is an unwieldy, change-resistant organization that operates according to its own logic and probably always will. Incidentally, he adds, “managers talk about employees like they’re numbers. You’ll hear them say things like, ‘This guy thinks he’s a five, but he’s such a three.’” Sam has one of the odder legal jobs in the United States, working in the biggest court system you probably never heard of. The state of California has over 1,800 judges, and claims to be the largest judicial system in the country. The federal judiciary had 792 active judges as of this summer. In between, with a little over 1,400 judges as of this summer, is the enormous, mostly hidden court system of the SSA. Though it lags behind California both in terms of judges and dispositions, the Supreme Court in 2003 concluded that “the social security hearing system is probably the largest adjudication agency in the western world.” The SSA’s proceedings, which mostly involve disputes over disability claims, are “administrative law courts,” making them not a true judiciary. These belong to the executive rather than the judicial branch, and both the judges and the attorneys representing the SSA are technically SSA employees. Administrative law courts pepper a lot of big government bureaucracies, sometimes as a mechanism for resolving arbitrations or other claims involving workers. I’ve visited a few, including the NYPD’s much-maligned APU unit, an airless closet stuffed in the bowels of One Police Plaza in downtown Manhattan, where civilian complaints against police officers mostly go to die. Sam works in a national organization teeming with hundreds of lawyers, but few of them got there on purpose. “No one grows up saying they want to be an SSA attorney,” he laughs. A lot of his colleagues dropped out of the corporate law track, where working a million hours a week as an associate-slave for the far-off reward of a maybe-partnership quickly stops seeming worth it, the first time you notice your kids growing up without you. At the SSA, he notes, lawyers give up the dream of future riches from defending deep-pocketed corporate villains, but, “I work basically nine to five, I’ve got benefits, security, and a home life.” The job of an SSA lawyer, generally, is to present the government’s side of a disability claim. When claimants appear before SSA judges, the hearings are closed to the public, a fitting metaphor given the similarly out-of-sight disabled population. The CDC says one in four adults in America lives with some kind of disability, and the SSA is currently paying disability benefits to 8.2 million workers, plus another 13.2 million receiving SSI disability benefits, making about 21.4 million people overall receiving some kind of federal disability benefit. Depending on what metric one uses to count America’s employed equals roughly 16% of the workforce. Those millions of beneficiaries are receiving an average of about $1,260 apiece monthly, working out to about a $10 billion monthly payout, and over $100 billion a year. That doesn’t sniff the military’s base annual payout of $732 billion, but it’s a big enough number, and the SSA court system exists, in theory, to keep the number manageable. A private insurance company might simply deny all claims and force applicants to climb a bureaucratic Everest to get every dime. The SSA, thank God, does not do that, but its thinking on this issue isn’t exactly clear, either. One main reason is that the agency has a lot of eyeballs on it. It is perennially in the middle of a tug-of-war, between mostly Republican members of congress who watch its payouts like hawks in search of fraud — why worry about unnecessary jet fighter contracts when you can kick ordinary people off the disability rolls? — and Democrats who push it to resolve its case backlog to make sure as many claimants as possible get paid. Somewhere in the middle is a reality, where a great many people are genuinely disabled and need help, but there are also fraudulent claims the taxpayer should be protected from having to pay. The SSA officials who manage the legal staff are mostly incentivized to clear cases one way or another, as opposed to worrying primarily about winning. Spend too much time fighting cases, and a manager might see the Washington Post write a scathing headline about how 10,000 people died waiting for benefits. For a long time, it was rare enough to hear about an SSA office focusing on winning its cases that when one tried, it attracted academic notice. In one study conducted by Penn Law, researchers talked about how SSA attorneys in the District of Maryland reacted after 2008, when claimants won 70% of their cases in actual judicial proceedings (i.e. not before Administrative Law Judges). “To reduce this rate,” the researchers wrote, “an OGC lawyer formed a team of colleagues to focus on District of Maryland litigation.” The lawyers “met frequently to strategize” and settled on groundbreaking new techniques, like: “if an argument about a particular issue proved persuasive to one judge, the team would then use this argument when the issue next arose.” As a result of this new “focus,” attorneys in that district reduced their loss rate from 70% to just under forty percent in two years. As for the judges, even a quick glance at the case disposition list shows that just as in the regular civil judiciary, some are “deniers” and some are “awarders”: If you think this is because some judges are sympathetic to workers and others are not, you might be right, but you also might not be. According to Sam, because of the peculiarities of the system, it “takes about 2-3 times longer to write a decision denying benefits than it does approving benefits.” This might be because there are few appeals of decisions to award benefits, so judges don’t have to spend as much time making sure their decisions are airtight. Thus a heavy “awarder” might be a friend of the people, or he or she might just be lazy. In one example that made headlines, the SSA in 2010 lauded a series of judges for clearing cases. One Atlanta-based judge was hailed for disposing of 867 cases in three months, while just behind him was an Oklahoma City-based judge named Howard O’Bryan, Jr., who disposed of 348 cases in that same time period. This somehow drew the attention of Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn, who launched a study and denounced the Oklahoma judge for approving about 90% of claims. Within a few years after being called out, the judge began denying more than twice as many claims as he approved. All of which speaks to the SSA being one of the odder court systems in the world. An army of lawyers represents a single client, the United States government, that seems largely disinterested in winning, at times seeming more content to pay over a hundred billion dollars a year in claims than to give out gold stars in employee evaluations. Depending on your point of view, this may not be a bad thing, especially if the agency is focusing on actually processing claims over contesting them. Though the agency still struggles for a variety of absurd reasons (including a failure to update documentation it needs to judge cases) to clear its massive backlog, it has done better in recent years at reducing the size of its case mountain. Whether you're a one, a three, or a five, "it's a weird place," Sam laughs. I reached out to the SSA about its training video, and it hasn’t commented. Many of our clients are frustrated by the question because they have fallen behind on bills since being unable to work and are feeling a great deal of stress and anxiety about their financial situation. This question causes a lot confusion because Social Security words it poorly.

The information that Social Security is looking for when asking this question is not whether you have enough money to pay your bills, but instead information like:

Notice that these questions above are focusing more about your ability to manage your money responsibly and not about whether you have enough money or credit available to meet your expenses month to month. When answering questions like this, think about examples of how you may need help from others to do things like organizing your budget, to physically write out checks or complete online payment forms. Being able to identify difficulties that you may have in these areas will give Social Security a better idea of what your needs and limitations are. Some disabilities, especially ones that are intellectual or emotional in nature, can interfere with someone’s ability to concentrate or remember to pay bills on time. Others can make it difficult for someone to resist the urge to spend money more impulsively. In some cases, Social Security may determine that a person is incapable of managing their own money because of their disabilities. In these cases, Social Security will appoint a person to act as your “Representative Payee.” This payee can be someone that you have chosen yourself, often a family member, but in rare occasions a professional third-party payee may be chosen on your behalf. The Payee’s role is to manage your money and to ensure that your living expenses and foreseeable needs are paid on your behalf with your benefits. If you would like to appoint someone to act as your Payee you will need to provide Social Security with that person's name and contact information. It is very standard for your disability officer to schedule a “consultative examination” for you in the Initial or Reconsideration stages of your disability claim. Social Security may decide that they do not have enough medical information about your physical or mental health from your medical records in order for them to make a proper medical determination in your disability claim. When this happens, Social Security may contract a medical professional to perform an independent examination. Although the Social Security Administration is paying the medical professional’s fee to perform the examination, that person IS NOT an employee of the Social Security Administration.

You should arrive at your examination with a photo ID at least 15 minutes prior to your appointment time. If you have any medical imaging (e.g. x-ray films, MRI imaging discs) you can take this with you to the appointment as well for the physician to review, but otherwise you do not need to take any medical records with you unless you have been specifically asked to provide them. The most important thing to keep in mind attending the exam is to try your best to cooperate with the examining physician and to be honest. Do not attempt to minimalize or exaggerate your symptoms. Answer all questions as accurately and in as much detail as you can. Avoid using absolute statements such as “always” or “never” and instead try to give examples or count how often (e.g. how many days a month) you experience your worst and best symptoms. When describing pain in your body, think about: where exactly in your body is the pain? Does your pain ever move/spread throughout your body? How many days out of a typical a week or month do you experience the pain? If your pain levels ever vary in intensity, what kinds of activities will make it better or worse? What kind of specific things are you limited from doing because of your pain? How does your pain affect your ability to do other things such as thinking, sleeping, or concentrating? When answering questions on questionnaire forms or speaking with doctors, it is always best to give detailed answers and to give examples. Notice how different the following statements are: “I have a bad back. My back hurts all the time and I can never do anything because of it. I have pain medicine the doctor gave me but it doesn’t do anything.” While this statement may be true, it does not give the doctor a lot of information. Now read this: “I have constant pain in my lower back, but it sometimes will move into my upper back in between my shoulders if I have to use my hands or arms a lot. It can also move into my hips and down my left leg if I have to be on my feet or walk a lot. I always have some difficulty lifting more than 30 pounds, pushing the lawnmower, or riding in a car for more than a few hours, but on days when I have the worse stiffness in my back I am not able to do these things at all. I do always have back pain but some days are worse than others -- especially if I have a day when I do a lot of chores or if I am really active. When my pain gets really bad I try to change positions or lie down for a few hours or sometimes take a pain pill. When my back pain is at its worst it keeps me from being able to sleep and I have a difficult time concentrating and feel irritable. On those days I have to take a sleeping pill or have to sleep in a recliner chair to keep my legs propped up and keep me from rolling too much.” The second story gives a lot more information about what types of things effect your pain and how your pain affects your ability to go about your daily life. This much detail gives the doctor and Social Security real life examples of what you’re dealing with on a daily basis. After your examination, the medical professional will write up a report and send that to your disability examiner. That person will use the report, along with the other medical records in your file and any other questionnaires you have already completed to make a decision in your claim. Reblogged from https://blog.ssa.gov/new-guidance-about-covid-19-economic-impact-payments/

"People who receive Social Security retirement, survivors, or disability insurance benefits and who did not file a tax return for 2018 or 2019 and who have qualifying children under age 17 should now go to the IRS’s webpage at www.irs.gov/coronavirus/economic-impact-payments to enter their information instead of waiting for their automatic $1,200 Economic Impact Payment. By taking proactive steps to enter information on the IRS website about them and their qualifying children, they will also receive the $500 per dependent child payment in addition to their $1,200 individual payment. If Social Security beneficiaries in this group do not provide their information to the IRS soon, they will have to wait to receive their $500 per qualifying child. The same new guidance also applies to SSI recipients, especially those who have qualifying children under age 17. To receive the full amount of the Economic Impact Payments you and your family are eligible for, go to the IRS’s Non-Filers: Enter Payment Info page at www.irs.gov/coronavirus/economic-impact-payments and provide information about yourself and your qualifying children. Additionally, any new beneficiaries since January 1, 2020, of either Social Security or SSI benefits, who did not file a tax return for 2018 or 2019, will also need to go to the IRS’s Non-Filers website to enter their information. Lastly, for Social Security retirement, survivors, or disability beneficiaries who do not have qualifying children under age 17, you do not need to take any action with the IRS. You will automatically receive your $1,200 economic impact payment directly from the IRS as long as you received an SSA-1099 for 2019. For SSI recipients who do not have qualifying children under age 17, we continue to work closely with Treasury in our efforts to make these payments automatically. Please note that we will not consider Economic Impact Payments as income for SSI recipients, and the payments are excluded from resources for 12 months. The eligibility requirements and other information about the Economic Impact Payments can be found here: www.irs.gov/coronavirus/economic-impact-payment-information-center. In addition, please continue to visit the IRS at www.irs.gov/coronavirus for the latest information. We will continue to update Social Security’s COVID-19 web page at www.socialsecurity.gov/coronavirus/ as further details become available." In light of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, our office will be conducting all consultations and appointments via telephone appointment. Please contact us at 502-456-0078 to schedule your appointment and make sure to give us the best telephone number to reach you by.

If you currently have a court date scheduled in the Jefferson Family Court, we will be in contact with you as most hearings have been postponed. If you have a hearing scheduled before the Social Security Administration, at this time these are going on as scheduled but we will be in contact with you if this changes. Because we understand that a lot of our clients may be medically frail or otherwise may be uncomfortable meeting with our office during this recent climate of COVID-19 outbreak, please know that we are perfectly happy to reschedule or to conduct our consultations over the telephone. If you are not able to come to the office during your appointment time, please contact us at 502-456-0078 to notify us that you would prefer to handle your appointment over the phone. We are happy to mail or email any documents we need for you to review or sign after we have had an opportunity to discuss your case with you.

Please understand that if you have received a notice of denial in your Social Security claim, you still have sixty (60) days in which to file an appeal. If you will not be able to get into the office before that deadline you should contact the Social Security Administration at 1-800-772-1213 or visit www.ssa.gov immediately to notify them that you wish to appeal the decision.

|

|